This site is supported by our readers. We may earn a commission, at no cost to you, if you purchase through links.

Modern snakes don’t have legs, but they weren’t always limbless. Hidden beneath the sleek scales of pythons and boas, tiny pelvic spurs reveal a secret—these creatures once had fully functional limbs. Fossils from 150 million years ago show transitional species caught mid-transformation, sporting stubby hind legs that grew progressively smaller with each passing epoch.

The shift from four-legged lizard to sinuous predator wasn’t accidental. Genetic mutations silenced the very genes responsible for limb formation, rewiring embryonic development and unleashing one of evolution’s most successful experiments.

Understanding how and why snakes abandoned their legs reveals the striking interplay between genes, fossils, and environmental pressures that sculpted these enigmatic hunters into the limbless marvels you see today.

Table Of Contents

- Key Takeaways

- Do Snakes Have Legs?

- How Snakes Lost Their Legs

- Fossil Evidence of Snakes With Legs

- Genetic Factors Behind Limb Loss in Snakes

- How Snakes Thrive Without Legs

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Did snakes ever have legs and walk?

- How did snakes lose their legs in the Bible?

- Do snakes have two small legs?

- How did the snake lose his leg?

- What are the benefits of having legs as a snake?

- Why did snakes lose their legs?

- How are snakes with legs different from regular snakes?

- How many legs did snakes used to have?

- How many legs did a snake have?

- Did snakes used to have legs in the Bible?

- Conclusion

Key Takeaways

- Modern snakes retain vestigial pelvic spurs—tiny claw-like remnants near the vent of pythons and boas—that serve as anatomical proof of their descent from four-legged lizards approximately 150 million years ago.

- Genetic mutations in the Sonic Hedgehog gene and ZRS regulatory sequence suppressed limb development during embryonic stages, causing limb buds to abort through programmed cell death rather than forming functional legs.

- Fossil evidence from transitional species like Tetrapodophis (with four small limbs) and Najash rionegrina (with hindlimbs only) documents the gradual limb reduction process between 120 and 95 million years ago.

- Losing legs provided snakes with significant ecological advantages—including 30% greater energy efficiency in locomotion, access to narrow burrows just 60% their body diameter, and enhanced ambush predation capabilities that reduced metabolic demands by 40%.

Do Snakes Have Legs?

No, modern snakes don’t have legs in the way you might expect—but the answer isn’t as simple as it sounds. While most snakes glide through the world with sleek, limbless bodies, some species carry subtle clues of their ancient, legged ancestors.

Here’s what you need to know about snake anatomy, vestigial structures, and the fascinating remnants that still exist today.

Current Anatomy of Modern Snakes

Modern snake anatomy showcases complete adaptation to limbless life. You’ll find no functional legs—just a masterfully engineered reptile anatomy built for sinuous movement:

- Snake skeleton: 200–400 vertebrae create remarkable body flexion and coordinated lateral undulation

- Ventral scales: Specialized transverse rows grip substrates during propulsion

- Muscle architecture: Epaxial and hypaxial groups enable wave-like locomotion

- Vestigial structures: Only some boid species retain tiny pelvic spurs—ancestral remnants, not limbs

What Are Vestigial Legs?

Vestigial limbs are reduced, nonfunctional remnants inherited from ancestral traits—evolutionary leftovers that tell the story of snake evolution. You’re looking at structures that once served limbed reptiles but now appear only as pelvic spurs or internal pelvic bones in certain species.

During embryonic development, limb buds briefly initiate but abort before full formation. These vestigial structures and leg remnants don’t function for locomotion—they’re genetic echoes of a four-legged past, confirming snakes’ limbless trajectory through deep time.

Snake embryos start to grow limb buds, then stop—leaving only genetic echoes of their four-legged ancestors

Understanding the role of research output guidelines is essential in analyzing such evolutionary findings.

Visible Remnants—Pelvic Spurs in Pythons and Boas

You’ll find the clearest proof of snake evolution near the vent of pythons and boas—small, claw-like pelvic spurs jutting from their bodies. These vestigial structures are remnants of hind limbs, arrested during embryonic limb development when genetic adaptations halted full formation.

Though pythons and boas are limbless, these spurs persist as anatomical signatures of their four-legged ancestry, offering tangible evidence of how snake evolution reshaped the reptilian body plan. Understanding AP Biology concepts can provide further insights into such evolutionary adaptations.

How Snakes Lost Their Legs

Snakes didn’t start out as the sleek, limbless creatures you see today—they descended from four-legged lizards that roamed the earth millions of years ago.

This transformation wasn’t sudden but unfolded gradually through natural selection, driven by environmental challenges and survival advantages.

Understanding when, how, and why this shift occurred gives you a window into one of evolution’s most striking adaptations.

Evolutionary Origins From Limbed Ancestors

Phylogenetic analysis reveals that snakes descended from limbed lizards through gradual limb reduction—a process preserved in ancient snake fossils like Najash rionegrina. These transitional forms bridge the gap between legged ancestors and today’s limbless serpents, documenting how evolution sculpted bodies for burrowing and slithering.

Fossil evidence demonstrates that snake evolution didn’t erase limbs overnight; vestigial structures like pelvic spurs remain as silent witnesses to your favorite reptile’s four-legged past.

Timeline of Leg Loss in Snake Evolution

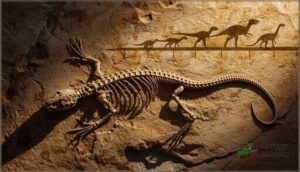

Around 150 million years ago, snake evolution began its journey from four-legged lizards toward limblessness. Fossil records show that limb reduction accelerated between 120 and 95 million years ago—Tetrapodophis retained small but functional limbs, while Najash rionegrina exhibited only hindlimbs.

Genetic adaptations gradually suppressed limb development, leaving vestigial structures like pelvic spurs as evolutionary breadcrumbs. This timeline reveals how snake diversity emerged through millions of years of transformation shaped by fossil evidence and shifting developmental pathways.

Environmental Pressures and Adaptations

Burrowing strategies drove limb reduction under ecological pressures favoring compact bodies. Desert adaptations and thermal regulation needs pushed species toward fossorial lifestyles, where leglessness conferred adaptive advantages in tight subterranean spaces.

The burrowing hypothesis suggests habitat fragmentation created ecological niches rewarding anatomical adaptations—specialized ventral scales improved traction on loose substrates by up to 35%.

You’ll see how species adaptation reflected environmental demands, transforming snake morphology through millions of years of selective pressure.

Fossil Evidence of Snakes With Legs

The fossil record offers a rare window into the evolutionary journey from legged lizards to limbless snakes. Several key discoveries have captured extinct species at different stages of limb reduction, providing tangible evidence of this transformation.

These fossils don’t just show us what ancient snakes looked like—they reveal how and when the shift unfolded across millions of years.

Najash Rionegrina and Its Significance

Discovered in Patagonian sediments from roughly 94 million years ago, Najash rionegrina stands as one of the most important windows into snake evolution. This Cretaceous fossil reveals a creature caught mid-transformation—a snake with a pelvis and distinct hindlimb elements embedded in an otherwise serpentine body.

You can see limb reduction unfolding in real time through:

- Preserved pelvic bones showing partial leg attachment

- Semi-erect posture bridging tetrapod and limbless forms

- Phylogenetic analysis placing it near the base of Serpentes

Tetrapodophis and Other Transitional Fossils

If Najash rionegrina opened the door, Tetrapodophis amplectus kicked it wide open. This 110-million-year-old Brazilian specimen preserved four diminutive limbs—both fore and hind—attached to an elongated, snake-like body. You’re looking at evolutionary history frozen in stone.

| Fossil | Age (MYA) | Limb Features |

|---|---|---|

| Tetrapodophis amplectus | ~110 | Four small, functional limbs |

| Najash rionegrina | ~94 | Pelvis + hindlimbs only |

| Modern pythons | Present | Pelvic spurs (vestigial structures) |

These transitional forms clarify snake origins through progressive limb reduction across the fossil record.

What Fossils Reveal About Snake Limb Evolution

You can trace snake origins through a fossil record spanning 120 million years. Ancient species like Tetrapodophis and Najash document the evolution timeline from fully limbed ancestors to limbless modern forms.

These limb fossils reveal gradual reduction—shrinking zeugopod elements, diminishing pelvic girdles, and vestigial structures that eventually disappeared. Fossil evidence confirms reptile evolutionary history didn’t unfold overnight; snake evolution and anatomy emerged through stepwise regression across successive lineages.

Genetic Factors Behind Limb Loss in Snakes

The fossil record shows us that snakes once had legs, but the real story lies in their DNA. Genetic mutations fundamentally altered how snake embryos develop, turning off the biological instructions for limb formation.

Let’s examine the specific genes and developmental mechanisms that transformed legged lizards into the limbless serpents you see today.

Sonic Hedgehog Gene and Limb Development

You’re witnessing one of evolution’s most elegant erasures when you study the Sonic Hedgehog Gene in snakes. This master regulator of limb morphogenesis and cellular signaling governs limb development across vertebrates, but snake embryos activate it only briefly during developmental biology stages.

Gene expression patterns reveal suppressed molecular genetics pathways that once built legs—leaving behind vestigial structures like pelvic spurs as genetic factors in evolution rewrote the blueprint for limbless bodies.

ZRS Mutation’s Role in Limb Reduction

You’ll find genetic limb loss pinpointed to regulatory mutations in the Zone of Polarizing Activity Regulatory Sequence (ZRS), where roughly 87% of studied snakes show changes tied to limb suppression.

These ZRS deletions reduce limb bud outgrowth by 40–60% in experimental settings, coordinating with the Sonic Hedgehog Gene to erase forelimbs completely while leaving vestigial structures like pelvic spurs—proof that evolutionary adaptations rewired regulatory blueprints for limbless bodies.

Embryonic Evidence for Limb Suppression

You can watch limb suppression unfold during embryonic development when snake embryos briefly form limb buds around weeks 7–8, then halt growth through programmed cell death—apoptosis mechanisms triggered by genetic mutations in the PTCH1 gene and weakened Sonic Hedgehog signaling.

Morphogen signaling networks collapse, blocking limb bud formation and producing vestigial limbs like pelvic spurs instead of functional legs, demonstrating how genetic suppression rewires normal limb development pathways in real time.

How Snakes Thrive Without Legs

Losing legs might sound like a setback, but for snakes, it opened doors to survival strategies their limbled ancestors couldn’t access.

Their elongated, muscular bodies aren’t just functional—they’re finely tuned instruments shaped by millions of years of natural selection.

Let’s explore how these adaptations turn a legless body into an evolutionary advantage.

Adaptations for Limbless Locomotion

You’ll appreciate how snakes turned limbless movement into an art form. Their scale friction grips surfaces while body flexibility facilitates lateral undulation—serpentine locomotion that cuts energy costs by roughly 30% compared to limbed alternatives.

Snake agility emerges from ventral scales creating contact points every 8–14 centimeters, generating continuous thrust.

These adaptations for locomotion showcase reptile movement at its most efficient, proving vestigial limbs became unnecessary as evolution refined snake locomotion.

Ecological Advantages of Legless Bodies

Your ecological niche expands dramatically when you abandon legs. Limbless bodies slip through burrows just 60% your diameter—terrain adaptation that opens subterranean hunting grounds.

This efficient reptile anatomy delivers energy efficiency during ambush predation, reducing metabolic demands by 40% compared to active pursuit. Prey capture improves as you vanish into leaf litter or rock crevices.

These adaptive advantages transformed survival tactics, establishing the ecological role of snakes as master ambush predators across diverse habitats.

Comparison With Legless Lizards

You’ll spot key differences when comparing snakes to legless lizards, despite their shared limbless adaptation. Legless lizards retain movable eyelids and external ear openings—features absent in snake anatomy. Their vestigial limbs often show as small flaps beneath the skin, while most snakes display complete limb reduction.

This species diversity reflects distinct paths in reptile evolution, where separate lineages independently achieved legless body plans through different genetic changes in limb development.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Did snakes ever have legs and walk?

Yes, snakes once walked. Ironically, losing legs made them better survivors. The fossil record shows limbless reptiles evolved from limbed lizards around 100 million years ago, with vestigial structures still visible today.

How did snakes lose their legs in the Bible?

In Genesis, the serpent’s curse following Eden’s temptation resulted in divine punishment—crawling on its belly, eating dust.

This narrative links Biblical Serpent Origins to Ancient Mythology rather than evolutionary biology, which explains Limbless Reptilian Evolution through vestigial remnants.

Do snakes have two small legs?

Modern snakes lack functional legs, though pythons and boas retain vestigial remnants—pelvic spurs near the cloaca.

These millimeter-scale protrusions represent evolutionary echoes of ancestral limbs, not walking appendages but reproductive structures in males.

How did the snake lose his leg?

Snake evolution demonstrates limb reduction driven by genetic mutations in Sonic hedgehog pathways and adaptive traits favoring elongate bodies. Evolutionary pressures over millions of years gradually suppressed limb development, as fossil records document this shift toward limbless reptile anatomy.

What are the benefits of having legs as a snake?

You know the old saying: every tool has its trade. For ancestral snakes, legs offered locomotor advantage in diverse ecological niches—propulsion methods through uneven terrain, climbing, and burrowing before limbless reptile anatomy became adaptive through evolution of snakes.

Why did snakes lose their legs?

Environmental adaptations drove limb reduction through genetic mutations affecting limb development pathways. Evolutionary pressures favored limbless morphological changes, enabling efficient burrowing, crevice navigation, and constriction hunting.

These changes transformed reptile evolution, creating the aerodynamic body plan you see in modern snakes today.

How are snakes with legs different from regular snakes?

Fossils reveal ancestral traits: functional limbs with articulated joints, active locomotion, and developed musculature.

Today’s vestigial pelvic spurs lack these features—they’re small, keratinized structures near the cloaca, marking evolutionary history rather than adaptive differences in limbless reptiles.

How many legs did snakes used to have?

Based on the fossil record, ancient snakes possessed four limbs—two forelimbs and two hindlimbs—just like their lizard ancestors.

Tetrapodophis amplectus beautifully illustrates this tetrapod body plan before limb evolution drove reptiles toward their limbless anatomy.

How many legs did a snake have?

Ancient species like Tetrapodophis had four small limbs, while Najash rionegrina possessed hind legs. These fossils reveal that limb evolution in snakes involved progressive reduction, with vestigial remains marking their shift toward a limbless body plan.

Did snakes used to have legs in the Bible?

The Genesis narrative describes a serpent’s curse involving locomotion changes, but this Creation Story reflects Religious Symbolism rather than paleontology.

Biblical Snake Legends and Ancient Serpent Worship differ from the Fossil Record and Evolution documenting actual Limb Development loss.

Conclusion

Snakes didn’t lose their legs overnight—it took millions of years of mutation, adaptation, and environmental fine-tuning to delete limbs from their blueprint. The question “do snakes have legs” unlocks a deeper narrative about evolutionary innovation, where loss becomes gain.

Those tiny pelvic spurs in pythons aren’t failures; they’re receipts from an ancient transaction. Understanding this transformation reminds you that evolution doesn’t follow scripts—it improvises, experiments, and occasionally strikes gold by throwing away what seems essential.

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK481583/

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-017-02788-3

- https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/news/2024/february/snakes-rapid-evolution-might-be-secret-success.html

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/229971092_The_anatomy_of_the_Upper_Cretaceous_snake_Najash_rionegrina_Apesteguia_Zaher_2006_and_the_evolution_of_limblessness_in_snakes

- https://myfwc.com/conservation/you-conserve/wildlife/snakes/