This site is supported by our readers. We may earn a commission, at no cost to you, if you purchase through links.

If you’ve kept snakes in captivity for any length of time, you’ve likely encountered a respiratory infection—that persistent wheezing, the mucus buildup around the mouth and nose, the slow decline that doesn’t respond to standard care. What you might not realize is that viral pathogens are often the culprit, and two in particular have become increasingly common in captive collections: nidovirus and paramyxovirus.

These aren’t new threats, but they’ve spread dramatically through global trade networks and densely populated breeding facilities, making them impossible to ignore if you work with reptiles. Understanding what these viruses are, how they spread, and what they actually do to an infected snake will fundamentally change how you approach quarantine, diagnosis, and long-term care decisions.

The difference between catching an infection early and watching it devastate an entire collection often comes down to recognizing the signs and knowing your options.

Table Of Contents

- Key Takeaways

- What is Nidovirus in Snakes?

- Nidovirus Infection: Causes and Transmission

- Clinical Signs of Nidovirus in Snakes

- What is Paramyxovirus Disease in Snakes?

- Diagnosis and Management of Snake Viral Diseases

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- What is the nidovirus in snakes?

- What is adenovirus in reptiles?

- What snakes have paramyxovirus?

- Can humans get nidovirus?

- What is Paramyxovirus disease in snakes?

- Can snakes get adenovirus?

- What kills nidovirus?

- What is the neurological virus in snakes?

- How do nidoviruses and paramyxoviruses spread among snakes?

- Can snake diseases be transmitted to other pets?

- Conclusion

Key Takeaways

- Nidovirus and paramyxovirus are distinct RNA viruses causing severe respiratory infections in captive snakes, with nidovirus showing highest prevalence in pythons (27-37%) and paramyxovirus spreading rapidly through direct contact and respiratory droplets across multiple snake families.

- Both viruses spread efficiently through captive collections via direct snake-to-snake contact, contaminated equipment, and aerosolized respiratory secretions, with asymptomatic carriers silently shedding virus for over a year and creating persistent transmission risks.

- Clinical signs progress from early respiratory symptoms like nasal discharge and wheezing to severe pneumonia and neurological manifestations including seizures and paralysis, with mortality rates reaching 70-75% in severe outbreaks despite supportive care.

- No approved antiviral treatments exist as of 2025, making strict biosecurity protocols—including 4-8 month quarantine periods with multiple PCR tests, rigorous equipment sterilization, and environmental controls—your only effective defense against these devastating viral diseases.

What is Nidovirus in Snakes?

Nidoviruses are a group of viruses that can infect snakes and cause serious respiratory disease, especially in captive collections. Understanding what these viruses are, how they’re classified, and which snakes they affect is essential if you keep reptiles or work with them professionally.

Here’s what the science tells us about nidovirus in snakes.

Definition and Virus Classification

Nidoviruses in snakes are enveloped RNA viruses belonging to the order Nidovirales, classified within the family Tobaniviridae and subfamily Serpentovirinae. These serpentovirus genera use a unique replication strategy, producing nested messenger RNAs during infection.

Meanwhile, paramyxoviruses like ferlavirus represent an entirely different viral order—Mononegavirales—with negative-sense RNA genomes. Though both infect snakes and cause serious disease, their fundamental viral structures and genetic mechanisms differ markedly, requiring distinct diagnostic and management approaches.

Nidoviruses, particularly within the Pregatovirus genus, are single-stranded RNA viruses.

Nidovirus Taxonomy and Structure

To understand how nidoviruses fit into the broader viral landscape, you need to know their taxonomic placement. The ICTV classifies snake nidoviruses within family Tobaniviridae, subfamily Serpentovirinae—a grouping that reflects their shared genome organization and replication strategy.

These viruses possess positive-sense RNA genomes ranging from 26 to 33 kilobases, considerably larger than most RNA viruses. Their genome encodes essential replication machinery, including the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase and proofreading exonuclease, features that distinguish nidoviruses from other viral families infecting reptiles.

Recent studies have identified serpentoviruses in viperid and elapid snakes, expanding their known host range.

Host Range and Epidemiology

Where these viruses show up tells us plenty about transmission patterns. Python populations carry nidoviruses at rates between 27.4% and 37.7%, while boids remain considerably less susceptible at 2.4% to 10.1%. Colubrids fall even lower at 0.9%. This variation matters because it reflects:

- Genetic host susceptibility differences across snake families

- Captive density amplifying viral spread in breeding environments

- Global trade moving infected animals across continents

- Wild populations showing minimal documented infection rates

Nidovirus Infection: Causes and Transmission

Understanding how nidovirus spreads is critical to protecting your snakes, whether you’re keeping a single pet or managing a breeding collection. The virus doesn’t appear out of nowhere—it travels through specific routes and thrives under certain conditions.

Let’s look at the transmission pathways and risk factors that make some snakes more vulnerable than others.

Transmission Routes in Captive and Wild Snakes

How quickly can infection spread through your collection? Nidoviruses transmit through multiple pathways in captive and wild snakes. Direct contact between snakes speeds rapid spread, while fomite transmission via shared equipment and contaminated surfaces extends risk. Aerosol transmission through respiratory secretions proves particularly efficient in dense housing. Some nidoviruses show vertical transfer in embryos, though evidence remains limited. Chronic shedding—sometimes exceeding one year—means asymptomatic carriers silently introduce virus into populations.

| Transmission Route | Mechanism | Duration |

|---|---|---|

| Direct Contact | Snake-to-snake exposure | Minutes to hours |

| Fomite Spread | Contaminated equipment, substrates | Days to months |

| Aerosol Transmission | Respiratory droplets, airborne particles | Hours to days |

Risk Factors for Infection

When your snake falls ill, multiple factors converge to create vulnerability. Poor husbandry practices—such as inadequate temperatures, humidity control, and dirty enclosures—compromise respiratory defenses and enable viral establishment.

High stocking density accelerates transmission within collections. Biosecurity lapses, like shared equipment, further promote the spread of illness.

Stress from frequent handling, breeding pressure, or transport suppresses immunity. Underlying parasitism or nutritional deficiencies also increase risk.

Host species matter too; pythons show markedly higher prevalence than other families. Coinfections with parasites or bacteria worsen outcomes considerably.

Outbreak Patterns in Snake Populations

When outbreaks strike captive collections, they spread with alarming speed. Prevalence can escalate from under 10% to over 50% within months, with some facilities reaching 75% mortality within 20 months. Pythons—particularly green tree pythons—show the highest susceptibility, while boas and colubrids remain largely spared.

Nidovirus outbreaks in captive snake collections escalate from under 10% to over 50% prevalence within months, with some facilities reaching 75% mortality

Environmental conditions matter enormously; dense housing, poor biosecurity, and co-infections increase transmission. Geographic clustering reveals how quickly viral disease outbreaks propagate when quarantine fails or new animals introduce infection into naive populations.

Clinical Signs of Nidovirus in Snakes

When a nidovirus takes hold in a snake, the signs can be hard to miss—or deceptively subtle, depending on how the infection progresses. You’ll want to know what to look for, because early recognition makes a real difference in how you respond.

Let’s walk through the clinical signs that usually show up in infected snakes, from the respiratory problems that often appear first to the more serious systemic effects that can develop over time.

Respiratory Symptoms and Pathology

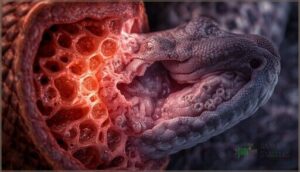

When your infected snake starts breathing differently, you’re likely witnessing proliferative pneumonia in action. Initial respiratory signs include increased oral and nasal mucus, progressing to wheezing and open-mouth breathing with audible sounds.

Histologically, lung tissue shows pseudostratified epithelial hyperplasia, nodular inflammatory cell accumulations, and marked interstitial inflammation—often with mucoid exudate obstructing airways.

Disease severity escalates rapidly; some snakes develop acute pneumonia within weeks, while others face sudden death from severe respiratory distress.

Systemic and Neurological Manifestations

Beyond respiratory trouble, nidovirus doesn’t stop at the lungs—it spreads throughout your snake’s body, creating widespread damage. This systemic dissemination involves multiple organs, causing liver, spleen, kidney, and pancreas involvement in severe cases. CNS involvement leads to neurological signs you’ll recognize:

- Star gazing, vertical head tilts, or opisthotonos

- Hindlimb paresis indicating lower motor neuron damage

- Seizure activity ranging from facial tics to convulsions

- Abnormal tongue flicking signaling progressing neurological involvement

Pythons generally show acute CNS deterioration, while boas develop chronic manifestations over months.

Disease Progression and Severity

Once nidovirus takes hold, you’re looking at a prolonged battle. Clinical signs emerge around four weeks post-exposure, escalating over ten to twelve weeks as respiratory scores climb from mild mucus to open-mouth breathing.

Mortality rates reach 75% in some populations, driven primarily by severe pneumonia and secondary bacterial infections. Most susceptible snakes succumb within six to twelve months, though chronic infections persist longer.

Some remain persistently positive for over a year, making disease duration unpredictable and management challenging.

What is Paramyxovirus Disease in Snakes?

Paramyxovirus is a different threat than nidovirus, though it shares some similarities in how it spreads through snake collections. You’ll find it affects respiratory function primarily, and it spreads quickly in crowded conditions—which is why understanding transmission patterns matters so much for your collection.

Here’s what you need to know about how this virus behaves and what signs to watch for.

Transmission and Epidemiology

Paramyxovirus spreads rapidly through both direct contact and aerosolized respiratory droplets, making it highly contagious in captive collections. Infected snakes shed the virus via oral and cloacal routes, and evidence suggests sexual and vertical transmission may occur through infected reproductive organs.

Population-dense environments like breeding farms show considerably higher infection prevalence than isolated snakes. Asymptomatic carriers can transmit the virus undetected, while environmental persistence on surfaces promotes horizontal transmission among housed snakes.

Clinical Signs and Disease Course

Paramyxovirus disease follows a predictable but serious progression. Your snake may show early symptoms like nasal discharge and open-mouth breathing in roughly 85% of cases, often accompanied by anorexia weeks prior. Disease progression generally accelerates within 2–4 weeks, with neurological signs emerging in about 22–33% of infected snakes. Mortality rates reach 70% in severe outbreaks. Chronic infections develop recurring secondary infections, with most snakes succumbing within 4–8 weeks of severe symptoms onset.

Key clinical manifestations:

- Respiratory distress and nasal discharge (85% of cases)

- Central nervous system involvement—head tremors, torticollis (22–33%)

- Emaciation and muscle wasting (62% of chronic cases)

- Secondary bacterial or fungal pneumonia (40% recurrence)

- Progressive neurologic decline preceding death (within 4–8 weeks)

Diagnosis and Management of Snake Viral Diseases

Catching a nidovirus or paramyxovirus infection early makes a real difference in how you manage your snake’s health. You’ll need to know what diagnostic tools are available to you, how to support an infected animal, and what biosecurity steps actually prevent these viruses from spreading through your collection.

Let’s walk through the practical strategies that work.

Diagnostic Methods (PCR, Histology, Serology)

When diagnosing nidovirus or paramyxovirus in your snakes, PCR remains your most reliable tool—it catches viral RNA with near-perfect accuracy in respiratory tissues. Histology helps identify characteristic lung inflammation, though it needs molecular confirmation for certainty.

Serology has real limitations: antibodies develop slowly, and cross-reactivity can mislead you. For the most dependable results, combine these approaches.

Emerging qPCR and multiplex methods now offer better species-level detection, giving you clearer answers faster.

Supportive Care and Biosecurity

Once you’ve confirmed nidovirus or paramyxovirus through PCR testing, your management strategy shifts to aggressive supportive care paired with ironclad biosecurity. Here’s what works:

- Fluid therapy at 15–25 ml/kg/day, adjusted for hydration status

- Heat supplementation to support immune function and recovery

- Oxygen therapy for snakes showing severe respiratory distress

- Parenteral antibiotics for 4–10 weeks, targeting secondary bacterial infections

- Strict quarantine lasting 4–8 months with three PCR rounds

These interventions greatly boost survival rates—up to 40% improvement when combined with rigorous biosecurity practices. Early intervention is your best defense against progression and spread throughout your collection.

Current Research on Treatments and Prevention

While supportive care buys time, the reality is stark: no approved antivirals exist yet for snake viral diseases. That’s changing. Remdesivir, ribavirin, and NITD-008 show promise in laboratory studies, though clinical application remains years away.

Heat therapy—raising temps to 35°C—has shown experimental success by slowing viral replication. Vaccine development lags due to viral diversity, but research continues.

Your immediate defense? Molecular diagnostics combined with rigorous quarantine protocols and biosecurity remain your most effective tools today.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the nidovirus in snakes?

Think of it as your snake’s immune system playing catch-up with a viral intruder.

Nidoviruses are enveloped RNA viruses classified under Serpentovirinae, causing respiratory disease primarily in pythons and other susceptible reptile species worldwide.

What is adenovirus in reptiles?

Adenoviruses of reptiles are DNA viruses causing viral disease in reptiles across multiple species. These reptile viral infections range from asymptomatic carriers to severe illness, affecting bearded dragons especially.

Adenovirus taxonomy includes three genera.

What snakes have paramyxovirus?

Regarding snake diseases, paramyxovirus infections don’t play favorites. Viperidae prevalence is highest, but Pythonidae susceptibility, Colubridae exposure, and Elapidae records show this viral disease affects multiple families, especially in captive prevalence situations.

Can humans get nidovirus?

No confirmed cases of human nidovirus infection exist as of

Research shows these viral pathogens remain host-restricted to reptiles, with significant transmission barriers preventing spillover, making their zoonotic potential extremely low.

What is Paramyxovirus disease in snakes?

Paramyxovirus infections in snakes cause a highly contagious viral disease. Symptoms include respiratory signs like wheezing and mouth breathing, as well as neurological symptoms such as tremors and seizures.

Outbreaks spread rapidly through respiratory secretions in captive collections.

Can snakes get adenovirus?

Yes, snakes can contract adenovirus. This viral disease in reptiles, while less common than nidovirus or paramyxovirus, still poses transmission risks in captivity, requiring diagnostic methods like PCR and supportive management outcomes.

What kills nidovirus?

You can inactivate nidovirus on surfaces using bleach efficacy, chlorhexidine solution, or ethanol effectiveness—each works within a minute. UV irradiation and thermal inactivation help too.

No antimicrobials cure infected snakes; focus on supportive care and biosecurity measures for reptiles.

What is the neurological virus in snakes?

Neurological signs in snakes stem primarily from viral diseases like serpentovirus (nidovirus) and paramyxovirus, which cause CNS involvement through viral neuropathology.

Envenomation effects also trigger neurological dysfunction, though viral transmission poses greater diagnostic challenges in captive collections.

How do nidoviruses and paramyxoviruses spread among snakes?

Think of a single infected snake as a match in dry grass—both nidovirus and paramyxovirus spread rapidly through horizontal transmission. This occurs via viral shedding in oral and respiratory secretions, fomite spread on shared equipment, aerosol infection, and bodily fluids. Such factors make snake quarantine essential for outbreak prevention.

Can snake diseases be transmitted to other pets?

Cross species risk from snake nidovirus and paramyxovirus to household pets remains negligible. These reptile-specific viral infections don’t transmit to mammals or birds, though standard household biosecurity prevents zoonotic diseases and viral spread through proper hygiene practices.

Conclusion

Think of your collection as a chain—only as strong as your weakest quarantine protocol. Snake diseases like nidovirus and paramyxovirus aren’t just academic concerns; they’re real threats that demand vigilance at every step.

Early detection through proper diagnostics, strict biosecurity measures, and informed decision-making separate successful keepers from those who learn these lessons the hard way.

You now have the knowledge to protect what you’ve built. Use it deliberately.

- https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/veterinary-science/articles/10.3389/fvets.2021.733404/full

- https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/mbio.00715-23

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8490724/

- https://academiccommons.columbia.edu/doi/10.7916/D8MS4489/download

- https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.10.036640v1.full-text