This site is supported by our readers. We may earn a commission, at no cost to you, if you purchase through links.

You’ll find snakes slithering through nearly every corner of the planet, from tropical rainforests to sun-scorched deserts, and they’ve split into roughly 3,900 species across 30 distinct families. Each type brings its own survival toolkit—some squeeze prey until its heart stops, others inject venom that shuts down nervous systems in minutes, and a few burrow underground like living earthworms.

The difference between a harmless garter snake and a deadly taipan isn’t just academic curiosity. Understanding how scientists group these legless hunters helps you recognize which ones pose real danger and which ones control the rodents raiding your garden.

From giants stretching longer than your car to thread snakes barely thicker than a pencil lead, the variety reveals millions of years of evolutionary problem-solving.

Table Of Contents

- Key Takeaways

- Snake Classification and Taxonomy

- Venomous Snake Species

- Nonvenomous Snake Types

- Snake Habitats and Adaptations

- Unique and Rare Snake Varieties

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- What are the 7 classifications of a snake?

- What is the top 10 biggest snake?

- How many types of pipe snakes are there?

- How many types of snakes are there?

- What are the different types of sea snakes?

- Where do snakes live?

- What is the top 10 snake?

- What are the 4 most poisonous snakes?

- What is the most common type of snake?

- What are common names for snakes?

- Conclusion

Key Takeaways

- Most snakes aren’t venomous—about 3,900 species split across 30 families, with nonvenomous constrictors and colubrids vastly outnumbering the dangerous ones you should actually worry about.

- Snake venom toxicity alone doesn’t determine human danger; the saw-scaled viper causes roughly 5,000 deaths yearly despite being less toxic than the inland taipan, because location and aggression matter more than raw potency.

- Scientists identify snakes through scale patterns, DNA barcoding, and now AI systems that reach 96% accuracy from photos, giving you reliable tools to recognize what’s slithering through your space.

- Snakes have evolved specialized adaptations for nearly every environment on Earth—from desert burrows to rainforest canopies to ocean depths—making them one of evolution’s most successful predators across 100+ million years.

Snake Classification and Taxonomy

Scientists organize snakes into groups based on shared traits, body structure, and evolutionary history. Right now, you’ll see how herpetologists divide snakes into major families and infraorders, plus the tools they use to tell one type from another.

Understanding this classification system helps you make sense of the amazing diversity hiding in the snake world.

Major Snake Families Explained

You’ll encounter snakes grouped into about 30 families worldwide, each with distinct characteristics that help you understand their behavior and risk level. This classification system—called family phylogeny—organizes over 4,170 species based on shared traits, venom potency, and evolutionary history. Here’s what matters most:

- Colubridae dominates with roughly 51% species richness across regional assemblages

- Elapidae includes cobras and sea snakes with potent neurotoxic venom

- Viperidae contains vipers and rattlesnakes with medically significant bites

Conservation status varies widely among snake families and characteristics. With approximately 3,600 known species, their diversity is striking.

Alethinophidia Vs. Scolecophidia

The suborder Serpentes splits into two major groups: Alethinophidia and Scolecophidia. Alethinophidia contains over 2,600 species—about 89% of all snakes you’ll recognize. These have well-developed eyes and occupy diverse habitats from treetops to oceans.

Scolecophidia, the blind and thread snakes, includes roughly 462 fossorial species with tiny vestigial eyes. Their evolutionary history traces back over 90 million years. Research indicates the idea of Scolecophidia’s paraphyly, suggesting Anomalepididae is a sister group to Alethinophidia.

How Scientists Identify Snake Types

You can identify snake species using several reliable methods. Scale pattern counts—especially the 15, 17, or 19 midbody dorsal rows—anchor traditional dichotomous keys that guide you through cephalic scales and subcaudal arrangements.

DNA barcoding compares mitochondrial genes to separate species with 2–4% divergence thresholds.

Venom proteomics profiles toxin families, while AI identification systems now achieve 96% species-level accuracy from photographs alone.

Venomous Snake Species

When you think about venomous snakes, you’re stepping into a world where evolution has turned a bite into a powerful survival tool. These snakes don’t all use their venom the same way—different families have developed distinct methods that reflect millions of years of adaptation.

Let’s look at the major groups of venomous snakes and what makes each one uniquely dangerous.

Elapids (Cobras, Mambas, Kraits)

When you think of venomous snakes, elapids like cobras, mambas, and kraits often top the list. These snakes deliver potent elapid venom through fixed front fangs, targeting your nervous system with neurotoxic compounds. Cobra hoods expand as a dramatic warning, while the black mamba’s speed reaches 20 km/h. Krait bites occur mostly at night, making them particularly dangerous in homes.

Key Elapid Features You Should Know:

- Venom Potency – The inland taipan’s venom has an LD50 of just 0.025 mg/kg, making it the deadliest on record

- Geographic Range – Over 360 elapid species span tropical and subtropical regions across six continents

- Conservation Status – Elapid conservation efforts focus on habitat protection, as some species face endangered status

Viperids (Vipers, Rattlesnakes, Adders)

Viperids—vipers, rattlesnakes, and adders—pack a punch with venom composition that causes swelling, tissue damage, and disrupted blood clotting. Their triangular heads and heat-sensing pits make physical adaptations unmistakable.

You’ll find these venomous snakes across Africa, Europe, Asia, and the Americas, though they skip Australia entirely. With 256 species spanning four subfamilies, viperid taxonomy reveals striking diversity, yet conservation threats like habitat loss endanger several species today.

Most Dangerous Venomous Snakes

When you’re weighing dangerous snake species, venom toxicity levels tell only part of the story. The Inland Taipan’s venom potency exceeds all others—one bite theoretically kills 100 people—yet it rarely encounters humans. Meanwhile, the Saw-scaled Viper causes roughly 5,000 regional fatalities yearly due to snake aggression and habitat overlap.

The deadliest snake venom doesn’t always mean the most human deaths—location and behavior matter more than toxicity alone

Antivenom efficacy dramatically improves survival rates, making snakebite treatment accessibility as critical as the venom itself.

Venom Delivery Mechanisms

Beyond fang length, venom delivery mechanisms determine how quickly snake venom affects prey. Four specialized systems have evolved to inject neurotoxins and cytotoxins effectively:

- Solenoglyphous fangs in viperids rotate forward and inject venom deeply through tubular teeth exceeding 2 cm

- Proteroglyphous fangs in front-fanged elapids deliver rapid shallow injections through fixed anterior teeth

- Opisthoglyphous fangs require prolonged chewing to transfer venom through grooved rear teeth

- Dentition plasticity permits replacement fangs to maintain continuous injection dynamics throughout life

Nonvenomous Snake Types

Most snakes you’ll come across don’t rely on venom to survive. Instead, they’ve developed other strategies like constriction, speed, or simply staying out of sight.

Let’s look at the main groups of nonvenomous snakes and what makes each one different.

Pythons and Boas (Constrictors)

You’ll recognize pythons and boas as powerful constrictors, though they’re distinct families—Pythonidae and Boidae. Pythons lay eggs (some species producing up to 100), while boas give birth to live young. Constriction mechanics work identically in both, squeezing prey until circulation stops.

Reticulated pythons reach over 10 meters, dwarfing most boas. Unfortunately, invasive pythons now threaten Florida’s ecosystem, demonstrating their adaptability outside native ranges.

Colubrids (Garter, Corn, King Snakes)

You’ll find Colubrids everywhere—they’re the largest snake family with over 1,900 species. Garter snakes thrive coast to coast, while corn snakes dominate the pet trade, raising invasive potential concerns in Brazil and beyond.

King snakes prey on venomous species thanks to venom immunity, even tackling rattlesnakes.

Though most nonvenomous Colubrids face fewer threats, some populations like San Francisco garter snakes remain endangered, requiring active conservation status monitoring.

Blind and Thread Snakes

You might walk past dozens of blind and thread snakes daily without noticing them—these tiny, worm-like fossorial adaptation masters rarely surface.

Here’s what makes these snake species noteworthy:

- Diet specialization: They feed exclusively on ant and termite larvae

- Global distribution: Found across tropical regions on six continents

- Reproduction strategies: Some reproduce parthenogenetically (all-female populations)

- Size range: From 10.4 cm Barbados threadsnake to 95 cm species

Their conservation status remains largely stable despite limited visibility.

Notable Nonvenomous Species

While blind snakes tunnel below, you’ll find nonvenomous snakes thriving above ground across diverse habitats.

Ball pythons demonstrate classic constrictor adaptations in African grasslands, reaching 182 cm. Corn snakes showcase colubrid diversity throughout the Southeastern United States, inhabiting forest openings up to 1,800 meters elevation.

California kingsnakes exemplify regional variations, measuring 1.8 meters and feeding on rodents and venomous snake species alike—their conservation status remains stable.

Snake Habitats and Adaptations

Snakes have adapted to nearly every environment on Earth, from trees and water to open deserts and dense forests. Each habitat has shaped how snakes move, hunt, and survive—whether that’s through specialized body types, unique hunting strategies, or coloration that helps them vanish into their surroundings.

Let’s look at how different snake types have evolved to thrive in their specific worlds.

Arboreal, Aquatic, and Terrestrial Snakes

When you’re learning snake identification, understanding where and how snakes move reveals key biomechanical differences. Arboreal species climb with slender bodies and specialized locomotion adaptations, while aquatic snakes swim using distinct muscle patterns. Terrestrial species like copperheads rely on ground-level cover and burrows.

This vertical niche partitioning shapes habitat complexity across ecosystems, directly influencing conservation status as development fragments these essential snake habitats.

Desert, Forest, and Grassland Species

Different snake habitats shape functional traits in striking ways. Desert species—over 30% fossorial in some North American regions—burrow through sandy soil with specialized shovel-nosed adaptations. Forest snakes climb vertically where canopy complexity allows, with arboreal species increasing alongside tree cover.

Grassland assemblages face urgent conservation status concerns as habitat specialization meets land-use impacts. Climate influence and vegetation structure determine which snake species thrive where you explore.

Coloration and Camouflage

Snake coloration and snake patterns serve striking camouflage functions through crypsis mechanisms—background-matching that hides individuals from predators and prey alike. Ontogenetic shifts in green pythons illustrate this: juveniles display bright yellow or red colors at forest edges, then shift to green as adults climb into canopy foliage.

Behavioral matching allows corn snakes to choose patterned substrates that enhance their concealment, while melanism prevalence reaches 31% across polymorphic species.

Aposematic signals, such as coral snake banding, warn predators of venom, demonstrating how snake adaptations balance concealment with survival.

Geographic Distribution of Snake Types

You’ll find roughly 80% of snake species concentrated in tropical and subtropical belts—latitudinal gradients that highlight continental diversity across the Neotropics, Afrotropics, and Indo-Malayan realms.

Habitat specificity shapes snake distribution within these zones, while island endemism produces unique lineages on archipelagos.

Urban adaptation now extends snake habitats into cities near green corridors, blurring traditional boundaries of snake classification and reshaping how you encounter diverse snake species globally.

Unique and Rare Snake Varieties

The snake world holds some truly exceptional outliers, from giants that stretch over 30 feet to miniature species you could coil around your wrist. You’ll also find individuals with striking color variations that break the mold of their species, and populations so rare that scientists work urgently to protect them.

Let’s look at what makes these unusual snakes stand out and why some deserve your attention for conservation reasons.

Giant and Dwarf Snake Species

When you think about size extremes among snake species, the reticulated python can reach 10 meters in snake length, making it the longest, while the Barbados threadsnake measures only 10 centimeters. These python proportions contrast sharply with dwarf adaptations in threadsnakes.

Constrictor mass also varies: green anacondas weigh over 97 kilograms, yet pygmy pythons stay under 1 meter. Both fill distinct ecological roles in their ecosystems.

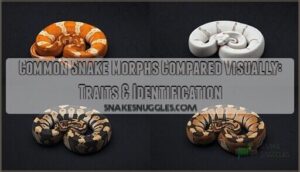

Unusual Color Morphs and Patterns

You encounter striking color morphs driven by melanism genetics and albinism causes in species like Emydocephalus annulatus, where melanic individuals reach 77.5% in males. Amelanistic corn snakes lack black borders due to OCA2 gene insertions, while albino ball pythons show TYR gene variants.

These pattern mutations create rare and unique snake names based on snake characteristics—lavender, axanthic, ultramel—each reflecting specific snake coloration tied to morph conservation efforts protecting color rarity in wild populations.

Endangered and Threatened Snakes

You’re witnessing a quiet crisis: approximately 421 snake species face extinction risk, with Critically Endangered, Endangered, and Vulnerable categories capturing nearly 10% of assessed snakes. Habitat loss and climate change drive population decline, hitting vipers especially hard—they represent 17–20% of threatened species despite being just 9% of all snakes.

Human impact through development, persecution, and fragmentation accelerates snake endangerment, making conservation efforts urgent for endangered species and threatened species survival.

Noteworthy Regional Snake Types

Certain regions host snakes that shape local snakebite patterns and conservation priorities. African vipers like Echis and Bitis cause up to 25,000 deaths annually in sub-Saharan zones, while Asian cobras—especially Naja naja and Russell’s viper—dominate India’s 81,000 yearly envenomings.

Australian elapids such as death adders lead Papua New Guinea incidents, and American crotalines, primarily copperheads and rattlesnakes, account for 99% of U.S. venomous bites.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the 7 classifications of a snake?

How do scientists organize thousands of snake species? The Linnaean hierarchy sorts snakes through seven taxonomic ranks—kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, species—establishing clear zoological classification from broad animal groups down to individual species within suborder Serpentes.

What is the top 10 biggest snake?

You’ll find the reticulated python at the top—lengths exceeding 20 feet make it the longest snake species.

Anacondas claim the title for sheer weight, though, tipping scales at 500 pounds with their massive bulk.

How many types of pipe snakes are there?

Pipe snake species counts vary depending on taxonomy. Asian pipe snakes (Cylindrophis) include 13–14 recognized species, while dwarf pipesnakes (Anomochilus) contain 3 species, totaling 16–17 types across these cryptic, fossorial lineages.

How many types of snakes are there?

Around 4,170 snake species inhabit Earth across 30 families, though undiscovered species likely exist. Species identification remains challenging, with misidentified specimens and naming conventions evolving as taxonomy advances.

This considerable diversity reflects millions of years of adaptation and classification refinement.

What are the different types of sea snakes?

Sea snakes inhabit tropical Indian and Pacific waters, split into two subfamilies: Hydrophiinae’s true sea snakes and Laticaudinae’s sea kraits.

Their paddle-like tails and laterally compressed bodies enable aquatic hunting.

Many species carry potent neurotoxic venom, making them among Earth’s most dangerous marine predators.

Where do snakes live?

Snakes inhabit nearly every continent except Antarctica, thriving across diverse environments. Your local snakes depend on regional climates—deserts in Australia, rainforests in Brazil, grasslands across Asia.

Habitat stratification determines whether species climb trees or stay ground-bound, shaping continental richness and microhabitat preferences worldwide.

What is the top 10 snake?

Ranking snakes depends on your criteria—venom potency, human fatalities, size, or temperament. The inland taipan dominates by toxicity, while the saw-scaled viper causes most deaths globally. Your “top” snake shifts based on what matters most to you.

What are the 4 most poisonous snakes?

The inland taipan tops the list with the most potent venom—025 mg/kg LD The eastern brown snake ranks second, causing most Australian fatalities.

Coastal taipans and tiger snakes follow, delivering neurotoxins that cause rapid paralysis and breathing failure without antivenom treatment.

What is the most common type of snake?

When you consider global distribution and human encounters, the common garter snake ranks as North America’s most widespread snake species.

Yet at the family level, colubrids dominate worldwide—nonvenomous prevalence means you’re statistically more likely encountering harmless colubrid types than venomous candidates across most populated regions.

What are common names for snakes?

Common names for snakes span broad group classifications like “vipers” and “colubrids,” iconic venomous types such as “cobra” and “mamba,” nonvenomous names like “python” and “garter snake,” and popular pet varieties including “ball python” and “corn snake.

Conclusion

You might assume snakes are either deadly or harmless, but recognizing the true types of snakes transforms how you move through natural spaces. That garter snake in your yard isn’t your enemy—it’s pest control.

Understanding which families kill through constriction, venom, or simply starving their prey gives you genuine power. Not fear. You’re now equipped to coexist with these fascinating hunters, protecting yourself while respecting the evolutionary brilliance that’s kept snakes thriving for over 100 million years.

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/pharmacology-toxicology-and-pharmaceutical-science/snake

- https://www.discoveryjournals.org/Species/current_issue/2022/v23/n71/A21.pdf

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5765514/

- https://viperconservation.org/threatened-species-list/

- https://research-management.mq.edu.au/ws/portalfiles/portal/103530137/103231323.pdf